FEMA has predicted that areas at risk of flooding in the United States would increase 45 percent by 2100, largely because of climate change. (Huffington Post)

–

The Federal Emergency Management Agency, in a study finally released last week after five years in the making, predicted that areas at risk of flooding in the United States would increase 45 percent by 2100, largely because of climate change. That prediction is dire news, not just for residents of flood zones, but for all taxpayers, who fund FEMA’s National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). With flood risk on the rise, the program will have to insure 80 percent more properties than it does today, and the average loss for each property could rise as much as 90 percent–an increase in payouts that our government can ill afford.

The ailing NFIP, which borrows taxpayer money from the Treasury to stay, well, afloat, is already one of the government’s biggest fiscal liabilities–it’s expected to go $25 to $30billion in debt after fulfilling claims from Hurricane Sandy–and is just one example of how global warming places tremendous stress on our economy. With its new study, FEMA at last joins a growing number of government agencies, including the Department of Defense and, more recently, the staid, nonpartisan, Government Accounting Office, warning that climate change is here–and that we need to be better prepared.

Today, the NFIP insures 5.6 million properties in flood hazard zones, the so-called “100-year” floodplains. These hazard zones, where the risk of flooding is one percent every year, are plotted on maps created by FEMA, based on historical data. But past flood records have proved to be a less-than reliable predictor of the extreme weather we’ve seen in recent years, or what we’re seeing this year, let alone what we’ll see next year. Carbon pollution in the atmosphere has been loading the dice in this annual gamble, turning once-in-a-lifetime risks into the new abnormal. Just ask the people of Binghamton, New York, hit by a “100-year” flood in 2005, a “500-year” flood in 2006, and then Tropical Storm Lee in 2011, prompting residents to ask, “What year flood is this?”

Or the Midwestern farmers who watched their corn shrivel in the fields during last year’s punishing drought, only to have to delay planting this spring because of heavy rains and record flooding along the Mississippi, Illinois, and other rivers.

Just ask private insurers like Allstate and State Farm, who started canceling policies in parts of Florida and Long Island years ago, no longer willing to face the enormous risks of coastal flooding and storm damages. While these insurers moved to disengage their business from a future of unsustainable losses, the NFIP continues to provide below-market-price insurance to flood-prone properties, essentially using billions in taxpayer money to subsidize people to live in harm’s way.

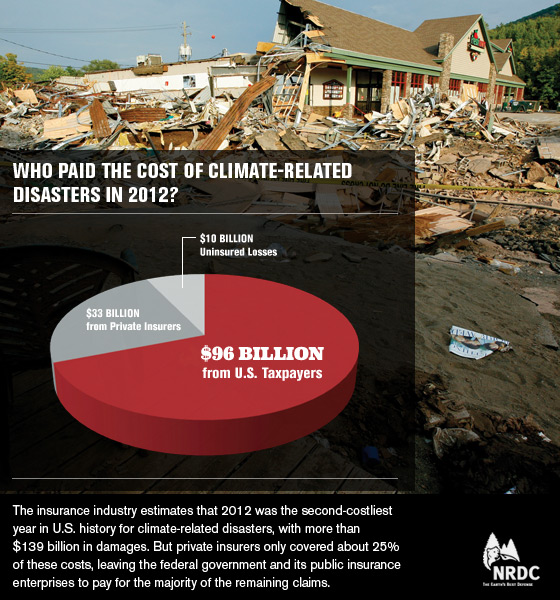

FEMA, which administers NFIP, has largely disregarded climate change in its calculations, until now. This analysis is long overdue. Last year alone, extreme weather caused $139 billion in damages, and taxpayers footed the bill for $96 billion of those costs. That’s more than we spent on education or transportation. That’s 8 times the budget of the EPA, and 8 times total government spending on energy.

In other words, we’re spending a lot more money on cleaning up after the fact than we are on solving the problem in the first place.

And we do know how to solve it. First, we can act now to slow global warming by cutting carbon pollution from its biggest source: power plants. President Obama can use his authority under the Clean Air Act to do this, and NRDC has an innovative, fair and flexible plan that can get it done quickly and cost-effectively.

Second, FEMA needs to factor climate change into state plans for dealing with disasters, instead of approving plans that rely only on historical data as an indicator of future extreme weather events. FEMA is an emergency management agency–it’s responsible not only for disaster recovery, but for helping states prepare and possibly avoid disasters in the first place. NRDC filed a petition with FEMA in 2012 asking them to do just this, but we have yet to get a response.

FEMA might be a little slow on the uptake, but some states and cities aren’t waiting to get climate smart. Cedar Rapids, Iowa, after a 2008 deluge left 14 percent of the city underwater and 10,000 residents displaced, began a voluntary buyout program for damaged homes and business to reduce the risk of future flooding. New York City recently doubled its estimate of city residents living in the 100-year flood plain in 2050 to 800,000 people. (By comparison, FEMA’s estimate, prior to Hurricane Sandy, was about 200,000 people.) The city aims to reduce its carbon pollution 30 percent, and is making plans to adapt its infrastructure to prepare for the increased likelihood and scope of storms and flooding.

In Nebraska, where climate change was once barely considered, the state’s Climate Assessment Response Committee is now required to evaluate the impacts of climate changeon water resources, agriculture, and other key sectors, as well develop recommendations to address these impacts.

More states and cities should start similar plans for climate change. With NRDC’s Climate Smart how-to guide on climate preparedness, there’s no excuse to follow North Carolina’s head-in-the-sand example. The state passed a law last year forbidding the consideration of climate change by state agencies in any decision-making. This is sheer folly, especially in a state where sea levels are rising 3 to 4 times faster than the global average.

Finally, flood insurance needs to be priced commensurate with its risks in order for the NFIP to survive. The program was meant to be a deterrent to building in flood plains, and instead, it’s become a resource that encourages developers to do so.

Failing to prepare for climate change not only affects those who live and work in the path of severe storms and wildfires, in flood plains and drought zones. It takes a broader economic toll on the nation, with very tangible costs for all of us.

As a parent, you tell your kids that it is easier to not spill in the first place than to clean up after a spill. In my career as an environmental lawyer, I saw that it was far cheaper to not dump toxic chemicals than to try to clean up afer they were in the ground. And now, on a larger scale, we’re seeing that it is cheaper to curb carbon pollution than it is to repair the damage caused by the extreme weather disasters brought on by climate change.

(Source: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/peter-lehner/new-fema-study-climate-ch_b_3467803.html)